Black Boys in Crisis: Lessons from the Central Park Five Tragedy

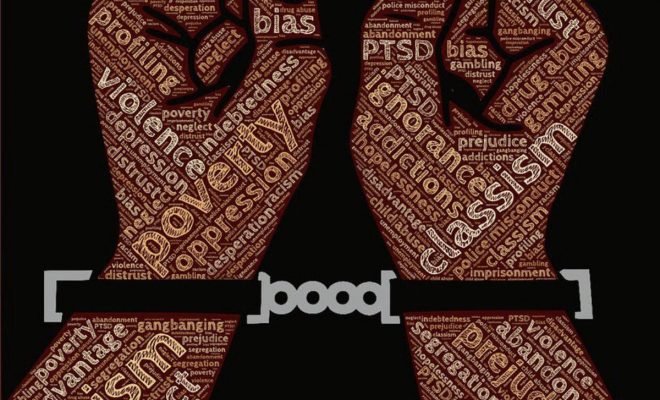

In this series, appropriately titled “Black Boys in Crisis,” I highlight the problems facing black boys in education today, as well as provide clear steps that will lead us out of the crisis.

In the spring of 1989, five black boys from Harlem were hauled into a New York detective’s office, accused of raping a white female jogger in Central Park. By the end of the night, all five had confessed to a crime they had not committed. The boys’ ordeal began after sundown in New York’s Central Park during a period of unusually high violence in the city. Their futures would be devastated by police coercion, a prosecutor hastily rushing to close the docket on a gruesome case, and public all too ready to believe white police officers over black teenagers. The boys would become known to the world as the Central Park Five.

Racial segregation had sharply divided the New York of the 1980s. At the turn of the decade, a surge in the market had created unimaginable wealth for New York’s upper classes; however, most of the working poor did not gain from the newfound prosperity. The crack epidemic of the mid-1980s caused violent crime to escalate at an unprecedented rate. The nights were peppered with gunshots and sirens. For commuters, rampant muggings meant that the simple walk from their apartments to their neighborhood train stations was fraught with danger. In this atmosphere of fear and constant unrest, New York’s poor black residents became the targets of police assaults and executions.

It was in this environment that, despite a lack of material evidence, detectives coerced five young men from Harlem into false confessions that permanently altered their lives. During the reign of terror of one of New York City’s most prolific serial rapists, detectives ignored the evidence linking the brutal attack to that assailant and decided instead to force five young men to fit the narrative police had constructed. Antron McCray, Raymond Santana, Kevin Richardson, Korey Wise, and Yusef Salaam entered a grim holding cell.

Separated from their families and support networks, they were subjected to psychologically traumatizing persuasion methods designed to extract confessions from the most hardened criminals. Each boy was shoehorned into what would become the worst miscarriage of justice New York residents had ever witnessed. Psychologist Saul Kassin estimated that the boys were confined in police holding cells for up to thirty hours without legal representation and suffered unrelenting abuse during that time. To make matters worse, the five young men found themselves at the center of a media maelstrom.

The flood of news reports (including graphic retellings of the events of the night in question) painted a tale of crazed boys running through the park at night, seeking victims on which to unleash their savage desires. “Wilding” was the media’s neologism to explain the uncontrolled and violent behavior that black New York City teenagers allegedly engaged in.

The events had a drastic effect on the lives of the teenagers. Antron McCray’s father made the decision to abandon his son and his mother after his first court appearance. In the documentary The Central Park Five, Antron McCray said, “My father, as the trial came, he left my mother and me. Disappeared. I couldn’t understand. I just hated him after that.” Sadly, McCray’s father passed away before he and his son could be reconciled. The five boys spent between six and thirteen years in prison. Following the confession of a serial rapist in 2001, the Central Park Five were acquitted of all charges in the case and were eventually compensated in a $40 million settlement in 2014.

As we saw in previous articles, the history of the black male in the United States is one of unrelenting stigmatization, categorization, and abuse. However, the story of the Central Park Five caught the public’s imagination and represented one of the first times white Americans had to reconcile their prejudices with reality. The vast majority of white Americans had been willing to believe the police narrative; the fact that all five boys had “confessed” was definitive proof of guilt in their minds. When the reality emerged, Americans were forced to confront their demons—demons of their own creation. They began to recognize for the first time the effect endemic racism was having on the lives of innocent young people.