Black Boys in Crisis: Kalief Browder and the Horrors of Incarceration

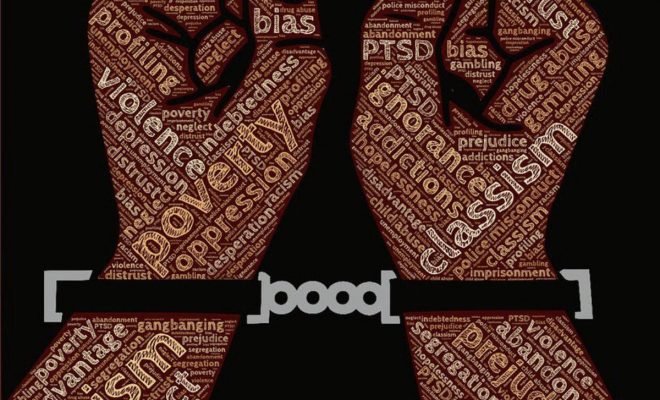

In this series, appropriately titled “Black Boys in Crisis,” I highlight the problems facing black boys in education today, as well as provide clear steps that will lead us out of the crisis.

Kalief Browder was a middle-of-the-road student. At sixteen, he was making mostly C’s, but his teachers called him “very smart, ” and he was well liked by his fellow classmates. He came from a broken home—his father had moved out when he was ten—but by all accounts, his mother was an astonishing caregiver. She raised seven children of her own and mothered over two dozen foster kids. Their two-story brick house in the Bronx was overflowing with love and nurture, and Browder had male role models he looked up to.

Like most young black boys in the Bronx, Browder had had some minor run-ins with the law. At one point, a couple of his friends had taken a delivery truck on a short joyride. Though Browder was an onlooker, he was charged along with them. But Browder had never been genuinely involved in a crime.

On May 15, 2010, Browder and a friend were walking home from a party when a police car pulled up alongside them. According to the officer, a man in a nearby police car claimed Browder and his friend had just robbed him. Browder denied it and asked the officer to search him. He had nothing on his person. The officer consulted the man, who then changed his story, claiming the robbery had been committed two weeks earlier. Again, Browder denied it.

Browder was taken to the precinct, and then to Central Booking at the Bronx County Criminal Court. Later, he was transported to the notorious Rikers Island prison. Thus began three years of nightmare. Unlike most other young black men who are taken to prison under dubious charges, Browder refused to take a plea bargain in exchange for admitting guilt. Instead, he insisted on his innocence and insisted throughout the process that he wanted a trial.

Unbelievably, the trial never came. Because of incompetent, overworked attorneys and a byzantine justice system, Browder’s trial was continually postponed: from December to January, from January to March, from March to June, and so on, over and over, until more than two years had passed. Though Browder could have taken the plea bargain, he kept insisting that he was innocent. His lawyer said, “Ninety-nine out of a hundred would take the offer that gets you out of jail. . . . He just said, ‘Nah, I’m not taking it.’ He didn’t flinch. Never talked about it. He was not taking a plea.” And meanwhile, the case against him was looking weaker: the accuser was waffling on the date the robbery had occurred. However, cases that actually go to trial are rare in the Bronx. In 2011, only 165 felony cases went to trial, while the defendant pleaded guilty in nearly 4,000 of them.

Life within Rikers, which is notorious for violence and abuse by both inmates and warders, was getting increasingly grimmer. At one point, Browder asked another inmate to stop throwing shoes. The argument escalated into a fight, and Browder was placed in solitary confinement. Around a quarter of the juvenile inmates at Rikers are in solitary confinement, which many claim is tantamount to torture. Certainly, in Browder’s case, it was a harrowing experience. There is no air conditioning in the tiny cells, and he became despondent and desperate. Over the next two years, he entered solitary confinement six more times, and he became suicidal. He tried to kill himself twice in prison, once with a noose made of bedsheets, once with a shard of a plastic bucket.

In his third year of incarceration, Browder got a new, more sympathetic judge. During his court appearance, she offered to release him that day, on time served, if he would simply agree to a couple of misdemeanors. He refused, saying, “I did not do it.” Later, at the prison, the other inmates thought he was nuts for refusing the plea bargain, but Browder was insistent that he was in the right: he wasn’t going to admit to guilt if he was innocent. Finally, on May 29, 2013, Browder’s case was dismissed: his accuser had returned to Mexico. Kalief Browder was released in early June.

Back at home, Browder exhibited classic signs of post-traumatic stress disorder. He found himself pacing, as he had in solitary confinement, and would lock himself in his room. Though he tried to date a few girls, they would always ask if he was in school or working. When he said he was at home, he reported that “They look at me like I ain’t worth nothing. Like I ain’t shit. It hurts to have people look at you like that.” According to Browder, “In my mind right now I feel like I’m still in jail because I’m still feeling the side effects from what happened in there.”

In June 2015, almost exactly two years after his release, Kalief Browder committed suicide. The lingering effects of his incarceration had broken his mind, and he couldn’t see a way through to a life worth living.

Ninety-five percent of those incarcerated in New York City are African American or Latino; that already astronomically high percentage rises when only youth are taken into account. It is almost more likely than not that a black boy from a low-income neighborhood, like Kalief Browder, will see the inside of a prison cell—even if he is demonstrably a decent student. And, as we saw in Browder’s case, the results of a stint in prison are catastrophic.

There is a growing crisis in our country surrounding the incarceration of African-American boys and men. The crisis is pervasive, and it is inextricably linked to the educational environment. Not only does an incarcerated adolescent boy lose months or years of education; he is often so traumatized that he is unable to make his way in the world.

Prison ends up teaching him what he knows about life, and when he gets out, he is likely to return to the cell. Recidivism rates are alarmingly high for black boys who have been imprisoned. This crisis affects not only the boys themselves and their families; it also affects communities, whose young male workers are removed from the picture, and who must deal with the undereducated, disenfranchised, and disenchanted men who emerge from prison.

There are two principal reasons for the school-to-prison pipeline for black boys. The first is a culture of educational discipline that treats kids as criminals. The second is endemic racism and greed in the American law-enforcement and justice systems. In subsequent articles in this series, we’ll look at both of these areas, as well as solutions to the problems.